-

أخر الأخبار

- استكشف

-

الصفحات

-

المدونات

-

المنتديات

Fallout co-creator says modern games "don't really know what they want to be," and I don't need to look too hard for examples

Fallout co-creator says modern games "don't really know what they want to be," and I don't need to look too hard for examples

The games of today, particularly triple-A games, are under intense pressure to perform. Hundreds of millions of dollars go into producing these behemoths, oftentimes necessitating mass appeal to make their money back and then some. However, going too broad can often be detrimental to their quality, resulting in a milquetoast game that fails to attract not only what should be its core audience, but players beyond its remit. Offering his own observations on how game design has changed since he started out in the '80s, Fallout co-creator Tim Cain emphasizes that modern devs should take notes from the efficient and focused development that defined that bygone era.

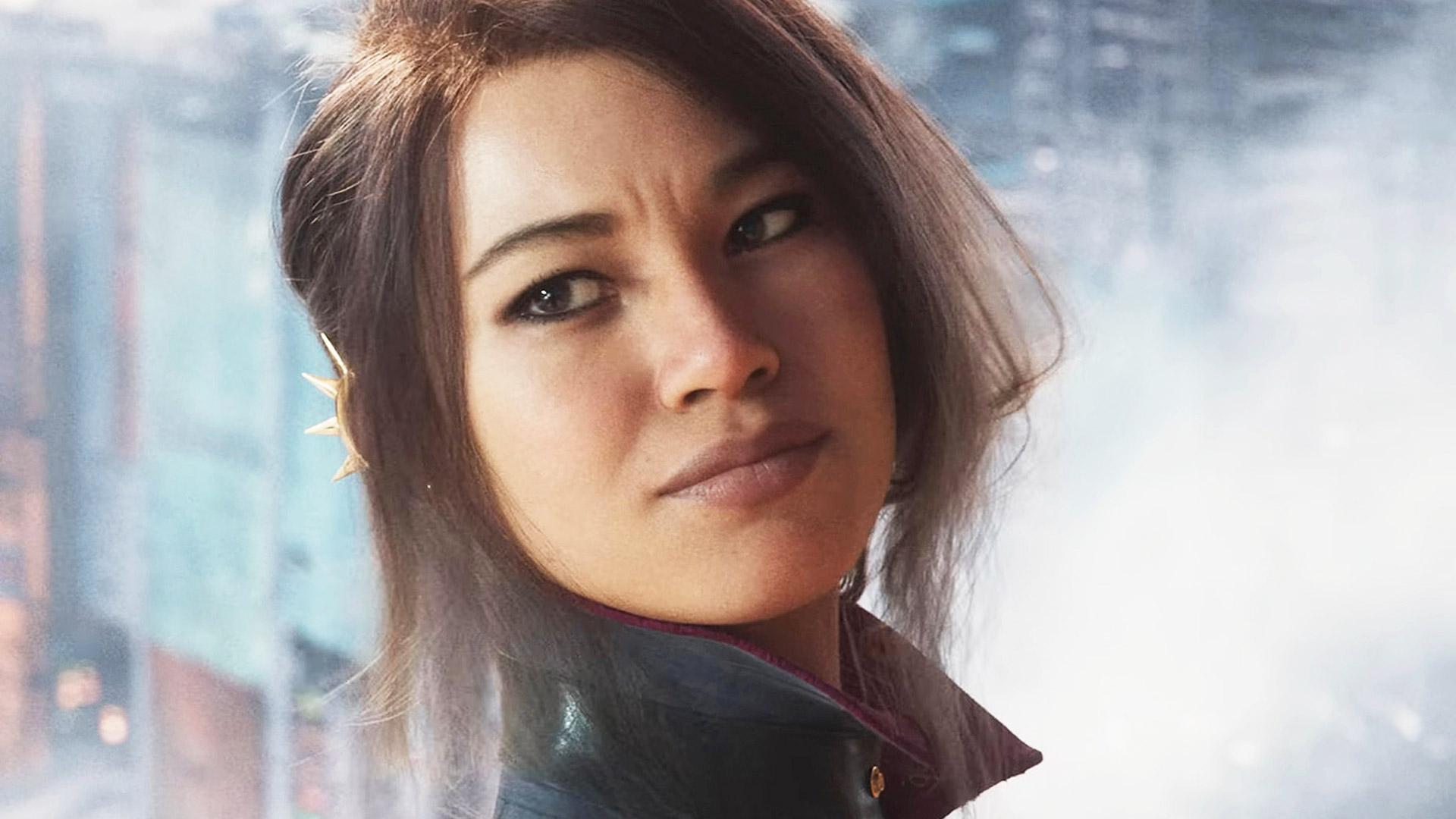

Now, obviously, there's a difference between games that have mass appeal because they executed so well that they became must-plays (think Skyrim and Baldur's Gate 3), and games that were designed specifically to appeal to the masses. Off the top of my head, the likes of Concord and, most recently, Killing Floor 3, have fallen foul of this. The former failed to establish a clear identity, crutching on well-established tropes to get its ideas across, while the latter watered down the more esoteric elements that made it iconic to try and be more approachable.

As Cain rightly points out in his recent musings: "An overriding possible issue with today's games is they don't really know what they want to be. They try to be everything to everyone: designed by committee, making a publisher happy, trying to guess what the largest demographic wants."

Conversely, Cain notes that back in the '80s, "games were really focused, because they had to be." This was an era where devs didn't have specialisms, and worked to incredibly tight hardware constraints. Minimalism was a fundamental part of the process. As Cain puts it, "It was 'you write efficient code, or your game doesn't work on the Atari console.'" As a result, focusing solely on the things that mattered to communicating a game's core concepts took center stage, by extension removing the pitfall of "becoming indulgent" modern games often tumble down.

If you take a look at the 2025 Game of the Year nominees, you can see the benefits of tight design. The likes of Expedition 33, Hades 2, Silksong, and Kingdom Come Deliverance 2 all shine because they're unabashedly themselves, and execute on their central pillars without muddying their creative vision with unnecessary chaff.

"Think of a fancy restaurant," Cain analogizes. "If you've ever been to really high-end restaurants, sometimes the most delicious dinners you've ever had have a very small set of ingredients." I think about the concept of 'subtraction is addition' a lot when working on music, or even in my day-to-day as a writer. Removing all the garnish nobody bothers eating, EQ'ing out ugly frequencies, and cutting down overly-wordy sentences all make for better results, and it's no different with videogames.