-

Feed de notícias

- EXPLORAR

-

Páginas

-

Blogs

-

Fóruns

First-Ever Look At Neanderthal Nasal Cavity Shatters Expectations

First-Ever Look At Neanderthal Nasal Cavity Shatters Expectations

The astonishingly well-preserved nasal cavity of a Neanderthal in Italy has finally settled one of the great debates in palaeoanthropology by completely contradicting our assumptions regarding the facial anatomy of our extinct relative. Previously, scientists thought that Neanderthals possessed specific structures in their noses that helped them deal with cold environments, yet we now know that these features did not actually exist.

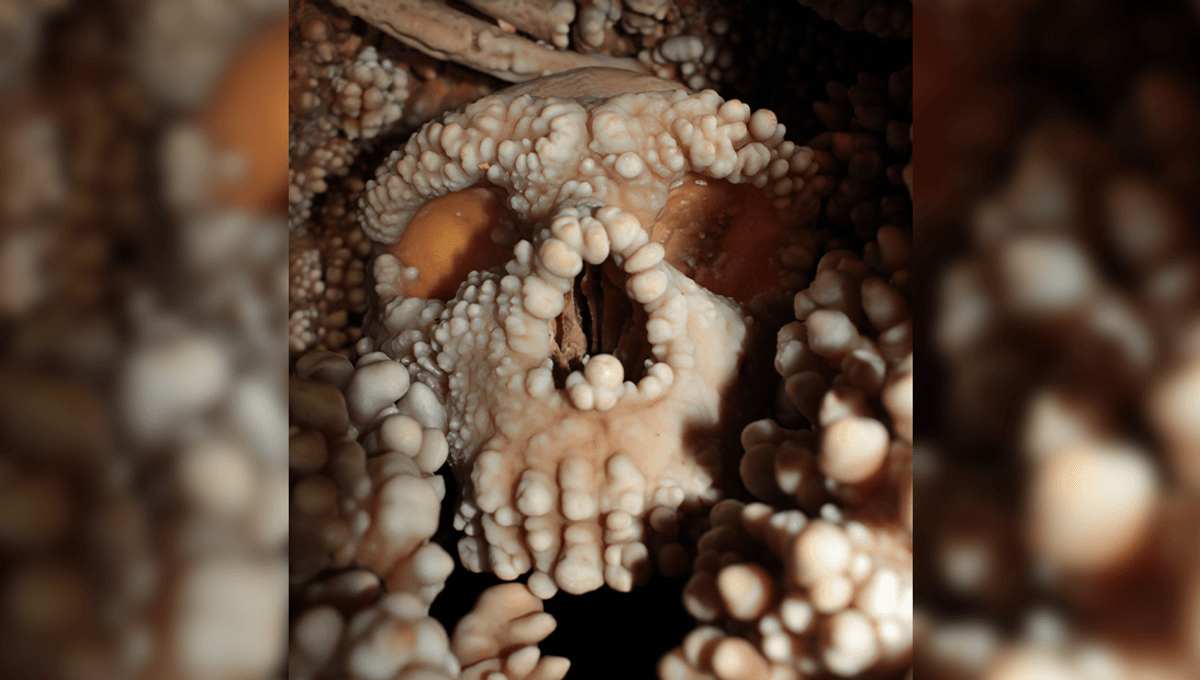

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Until now, no one had ever actually seen the inner workings of the Neanderthal nasal cavity, since the delicate bones inside the nose are too fragile to survive in the fossil record. However, researchers finally got their first glimpse at this morphology when studying the famous Altamura Man, whose skeleton remains trapped inside the Lamalunga karstic system in southern Italy. “The first time I got into the cave and realized how well preserved the nasal cavity was, I was amazed, because I have seen many crania in our labs and I know that these structures are often destroyed,” study author Costantino Buzi told IFLScience. Thought to be between 130,000 and 172,000 years old, the Altamura Man can’t be extracted from the cave as it is embedded in rock and covered in concretions called calcite popcorn coralloids, yet Buzi and his colleagues were able to digitally reconstruct the nasal cavity using endoscopic technology within the cave itself. Neanderthals had their own solution for adapting airflow for the cold climate. Costantino Buzi Despite never having seen the inside of a Neanderthal nose, experts had previously proposed the existence of certain autapomorphies – meaning traits that are unique to a particular species. Specifically, scholars had hypothesized that Neanderthals should possess a series of cold-climate adaptations, including a swelling on the nasal cavity wall and a lack of an ossified roof over the lacrimal groove. Based on the team’s findings, however, Buzi explains that “we can finally say these traits don't exist, so we can remove them from the diagnostic list of traits [for Neanderthals].” Indeed, in their new paper, the authors write that the inner nasal cavity of the Altamura Man is largely similar to that of modern humans, and that “no additional structures are recognizable.” A digital reconstruction of the nasal cavity of the Altamura Man. Image credit: Costantino Buzi More broadly, these findings provide new insights into the weirdly paradoxical appearance of Neanderthals, who possessed a body plan similar to that of cold-adapted modern humans from mountainous or high-latitude locations, but a large nasal opening that would be more suitable for someone from a warm, humid environment. Even in the absence of the hypothesized autapomorphies, however, Buzi insists that “we can say that this is no longer a paradox, because we can see that the inner structure of the nasal cavity is is consistent what with what we expect in a massive face – like that of Neanderthals – that should function in a cold environment.” “To put it simply, by looking at the interior portion of the nose, we can see that Neanderthals had their own solution for adapting airflow for the cold climate,” he says. “So they were cold-adapted in the face with a different model from our own.” The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.