-

Feed de Notícias

- EXPLORAR

-

Páginas

-

Blogs

-

Fóruns

50,000-Year-Old Collagen Could Lead Us To Hippo-Sized Wombats In The Fossil Record

Earth Once Had Wombats The Size Of Hippos, And Fossilized Collagen Could Be The Key To Finding Them

From around 50,000 to 10,000 years ago, Earth was home to terrestrial giants: mammoths, moa, and mega-marsupials, including something that "would have looked like a wombat the size of a hippo". We really had it all, until we didn’t.

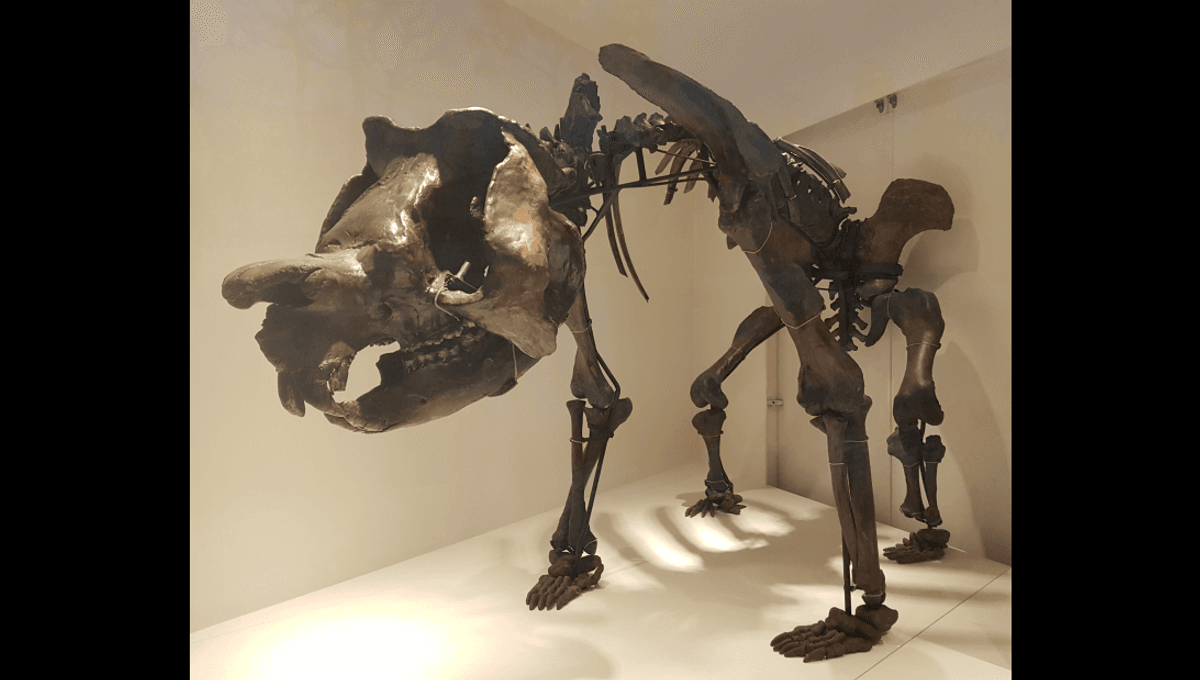

The disappearance of Earth’s megafauna remains something of a mystery, not least because we don’t have much fossil evidence to work from. It may sound surprising, but even very large creatures can be difficult to find in the fossil record. This can be a result of the environment in which they died, as fossilization varies greatly depending on how and where you popped your clogs. This is especially true in what we now call Australia, where hot damp environments have led to poor preservation of DNA and fossil fragmentation. The fossil record here can be sparse in places because, essentially, we’re working with tiny bits of incomplete information. If only there were some other way to test for what kind of dead animal speck you’d found… Lack of data means that it is difficult to test theories and hypotheses on why these animals became extinct. Dr Carli Peters Enter: Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (aka, ZooMS), a branch of palaeoproteomics that’s been used to taxonomically identify animal remains even in highly fragmented bone assemblages. It had previously been taken for a spin in Eurasian contexts, but a new study used the approach to search for peptide markers in fossil collagen for three extinct Australian megafauna: Zygomaturus trilobus, Palorchestes azael, and Protemnodon mamkurra. Not sure what any of those are? Here’s Professor Katerina Douka of the University of Vienna to explain: “Zygomaturus trilobus was one of the largest marsupials that ever existed — it would have looked like a wombat the size of a hippo,” Douka said in a release. “Protemnodon mamkurra was a giant, slow-moving kangaroo, potentially walking on all fours at times. Palorchestes azael was an unusual-looking marsupial that possessed a skull with highly retracted nasals and a long protrusible tongue, strong forelimbs, and enormous claws.” Collagen peptide markers are a good alternative when fossil preservation is a bit lacking because they're tougher than DNA. Sure enough, they discovered that ZooMS could identify animals from fragmented remains down to the genus level, and this could have big implications for the mysterious disappearance of megafauna. Now that we can use ZooMS to identify megafauna remains from collagen preserved in their bones, we can start identifying a larger number of megafauna remains in Australian paleontological assemblages. Dr Carli Peters “One of the main limitations in the study of megafauna extinctions in Australia is the low number of megafauna fossils that have been recovered from paleontological sites across the country,” said first author Dr Carli Peters, postdoctoral researcher at the University of Algarve, to IFLScience. “This lack of data means that it is difficult to test theories and hypotheses on why these animals became extinct.” “Now that we can use ZooMS to identify megafauna remains from collagen preserved in their bones, we can start identifying a larger number of megafauna remains in Australian paleontological assemblages. This, for example, could help us increase our understanding of the past geographic range of these animals. Through the identification of fragmented megafauna bones, we can also find specimens that are suitable for other types of analyses such as ancient DNA or stable isotope analysis.” So, if fossils can’t handle the conditions of Earth’s past, well that’s just fine. They can crumble into obscurity. Thanks to this new approach, if there’s collagen preserved (and we’ve found that stuff going even further back than T. rex), we can still find ways to study the ecology and eventual extinction of Earth’s extinct megafauna. The study is published in Frontiers in Mammal Science.