The World’s Oldest Known Snake In Captivity Became A Mom At 62 – No Dad Required

The World’s Oldest Known Snake In Captivity Became A Mom At 62 – No Dad Required

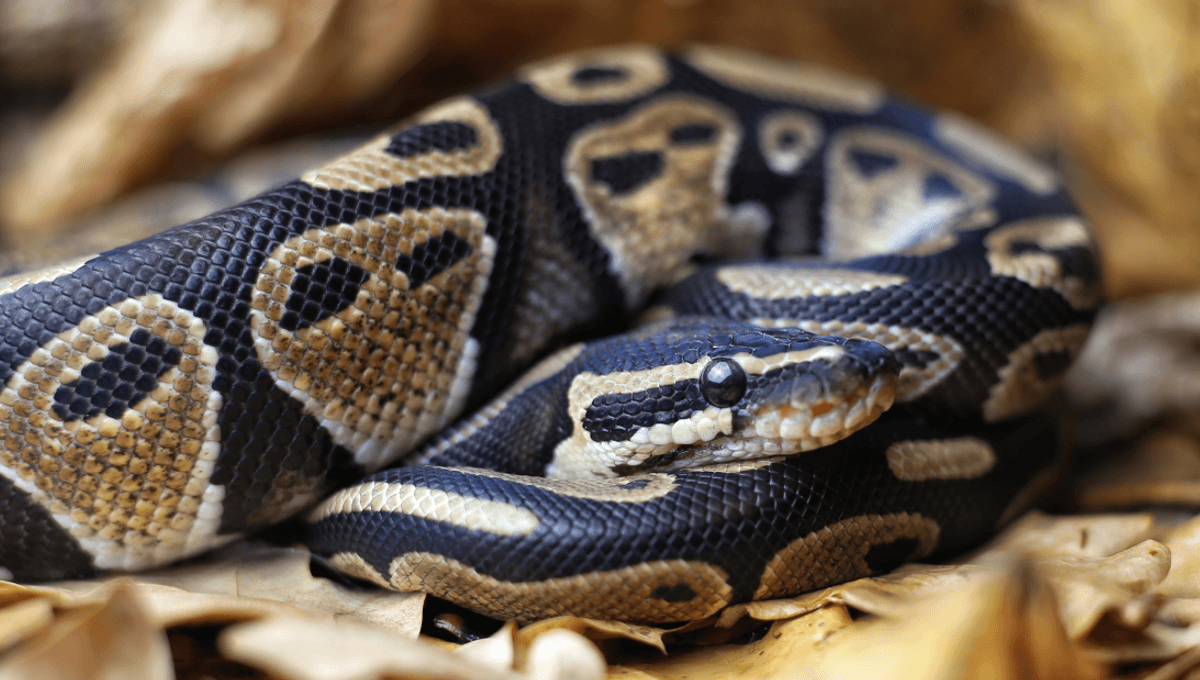

In 2021, the Saint Louis Zoo in Missouri lost a very special resident. She was a snake, but not just any snake. You see, this ball python was the oldest snake in the world in zoo care. She lived to a staggering 62 years old, but not before doing something remarkable just a year before her death.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. In 2020, the news broke that this ball python female had laid a clutch of viable eggs. It was unexpected for a snake in her sixth decade, and even stranger given the fact she hadn’t been in contact with a male for 15 years. Ball pythons (Python regius), also known as Royal pythons, are a species native to the grasslands of central and western Africa. The average ball python lives up to 30 years in captivity, so this individual was exceptionally old, especially for a mother-to-be. “She’d definitely be the oldest snake we know of in history,” Mark Wanner, manager of herpetology at the zoo, told the Associated Press in reference to her producing the eggs. According to an email from the zoo’s Guest Experience Department shared on Reddit, the snake passed away in 2021. Not surprising, given her great age compared to the average life expectancy of these snakes, but she left behind a small legacy. Of her clutch, two eggs hatched and one of those snakes survived. The zoo is now collaborating with its university research partner to ascertain if this really was a case of parthenogenesis – aka, “virgin birth”. The word parthenogenesis literally means “virgin creation” in Greek. It’s a form of asexual reproduction in which an egg develops into an embryo without needing to be fertilized. In animals, this entails making an egg through automixis so the egg can merge with cells called polar bodies, which are leftovers from the egg production process. This generates offspring that are similar to the mother but not exact clones, and they’re generally all female. We used to think parthenogenesis was rare, but it’s becoming increasingly clear that it’s not all that unusual, even in cases where females had access to males but decide reproduce solo anyway. It’s common among bees and tardigrades, and has been observed in over 80 taxa. Parthenogenesis isn’t the only way a female can reproduce without being in contact with a male, however. Some species are able to store up sperm or fertilized eggs and only kick off pregnancy when conditions are just right. Then there are always those zoo animals who manage to find a glory loophole.